It’s been a while since I wanted to dive into this topic. In fact, this topic has been exploring itself while I was exploring the beautiful city of Paris. This essay is a first account of elusive thoughts that came to my mind in the midst of the ongoing quest for experiences this city hides.

For more than 40% of us French people, cities are our alpha and omega. Cities layout and build up shape the ways we live in them: not only our professional and personal lives, but even the way we think and feel about the world.

In this essay, I’ll try and take a first cut at how I think they will evolve in the years to come.

Looking back

The will to transform cities is a long time in the making. Dating back to the haussmannian transformation of Paris to the rapid rise of the New York Skyline, to building Dubai from a small fishing location, cities have always fostered innovation for the way we organize space and interact with each other. Observing the renaissance and different phases of cities like Amsterdam, aka the birthplace of capitalism, is truly fascinating - Go check out that incredible documentary on the topic.

For the sake of simplicity, I would say there was three major disruptions in modern western cities :

The first major disruption was the industrial revolution. It came to replace a relatively stable urban system of the Middle Age redefining what the scope of business and accommodation needs in cities. Which in turn forced the public administrators of the time to imagine radically new systems to to deal with technical, sanitary and social issues . In France, Haussmann played a big role in redesigning Paris and influenced smaller cities

The second disruption came with the standardization of retail and office space. Started after the First World war, this movement has massively accelerated under the rebuild effort following WWII. Big retail stores went from a few iconic landmarks to multiple standardized retail chains. Massive malls made their entry in central districts, reshaping traffic planning. Which was further encouraged by the “all-car” spirit, best embodied in Paris and France by Georges Pompidou’s policies.

We are now facing the third wave disruption : spatial organization, urbanism, architecture and mobility are overwhelmingly driven by the sheer volume of data, social activism and climate concerns. While the previous two disruptions happened as a reaction to the problematic effects of change, this third wave is a product of anticipation. And the answer to those future problems can be best summed up by the concept of “smart city”.

Smart cities get thrown around by corporations and politicians a whole lot lately. For the most part serving the goal of keeping the right appearances: the once of virtue and forefront of anticipation Disclaimer: in reality, it rarely is the case.

Let’s try to cut to the chase and look at what really makes a city “smart”.

What makes a city “smart” ?

I think the concept of smart city is largely expressed through its fundamental trait : anticipation, anticipation, anticipation. This anticipation must be present in the three main layers of a city infrastructure :

Hardware and physical base. The first enabler is a critical mass of consumer devices (smartphones, consumer IoT products and sensors) and “stationery” sensors connected by high-speed communication networks and open data portals. Sensors log and compute constant streams of variables (such as traffic flow, energy consumption, air quality) and put information at the fingertips of the end user

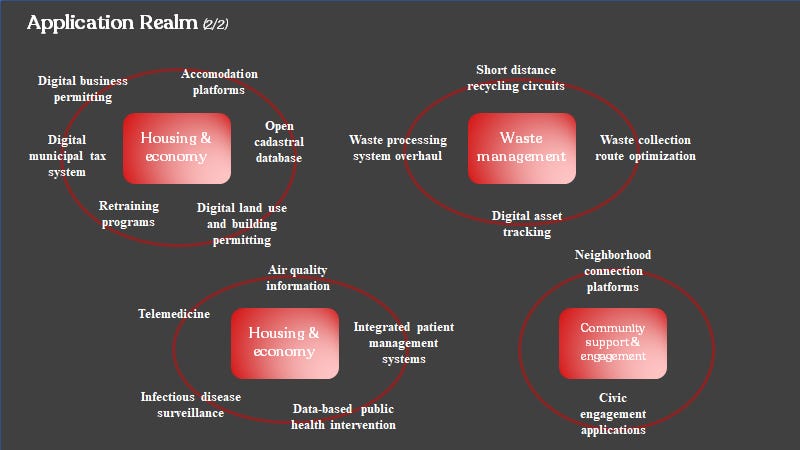

Software applications. They are needed to process and transform data into actionable insights, and this is where public and private technology providers and app developers come in. Perhaps the best way to grasp what a smart city can be is to look at the full sweep of currently available applications, I’ll include the list further in the essay !

Adoption and usage. Many applications succeed only if they are widely adopted and drive behavioral change. A number of them put individual users into the driver’s seat by giving them more transparent information they can use to make better choices

In the mapping below, we’ll try to sort out who’s building what in these different use cases, and perhaps uncover some gaps in this pretty theoretical mind-map.

This is a very large realm for early stage investors, and it taps into different stakes and investment philosophies. As an investor, even if you claim to be a smart city specialist (e.g. French top tier VC Idinvest has a dedicated team and fund for smart cities), you have multiple sub-themes to reflect upon. Those go along the lines of:

Am I going to be funding hardware innovation efforts for the physical infrastructure ?

Am I going to be funding pure software and data oriented developments with potentially great scaling potential ?

Or … A clever mix of both that has an attractive upside ?

Since it's impossible to cover all use cases, I have chosen to brush on several of my favorite topics in the broader topic of building the future of cities.

Focus #1 - The battle of street pedestrianization

Rapid proliferation of private automobiles in the 1950s caused car-centered urban planning. There were very sporadic examples of car bans before the 2000s - In Holland during the 1st oil crash of 1973 then in the Ciclovia initiative in Bogota (c.1975) .

The rapid rise in private car ownership and decline of public transport over the second half of the twentieth century has led to an air pollution crisis in most major cities around the world. 91% of the global population live in places that exceed WHO’s air pollution exceeds its guideline limits. It’s estimated that 4.2 million premature deaths are caused annually by ambient air pollution (via strokes, heart and pulmonary disease, cancer). Pollution is the biggest environmental risk to public health around the world

High-profile scandals like ‘Dieselgate’ and the deserted streets amidst lockdown have cause public opinion to turn faster against the domination of cars and some forward-thinking mayors have been willing to face the backlash and take action.

Enablers

Activism and action groups like Bogota Ciclovia and London Smog Day : the first ciclovia (Sunday without cars) was held in 1974, and latin american cities since have a long history of activism, which even spread to the USA, a.k.a. The Gaslit Nation in cities like Minneapolis. Those initiatives are light statements, but they hint at what’s possible should we collectively have the will to commit to less cars in entire neighborhoods. West European cities, in particular London and Paris, were trailing behind before the pressure mounted too far on their local politicians: it wasn’t until a few years ago that both organized their car free Sunday.

Changing political landscape in city mayor administrations. Evidence suggests that learning from other cities’ policies and successful implementation is also key – the example of Bogotá’s Ciclovía was replicated in hundreds of cities across Latin America, following its promotion through international events and global policy networks by sustainable transportation and public health advocates.

Shifting perceptions about car use. Most local governments face stiff opposition when first attempting to introduce pedestrianised zones or days, but the successful demonstration of car-free policies appears to support shifts in public opinion that can promote policy expansion. In Oslo, initial plans to pedestrianise the centre of the city overnight were scaled back to allow for a gradual implementation of pedestrianisation policies to ensure the support of local residents. In Bogotá, following the success of the weekly Ciclovía, a referendum was held where Bogota residents were asked to vote on an annual car free weekday which covers the entire expanse of the city’s 28,153 hectares. 63% of Bogotanos voted to make the event a permanent fixture in their calendar

Focus #2 - Greenfield approaches to smarter neighborhoods

While the majority of founders and investors are focused on building upon the existing city infrastructure, some have taken a radically different approach : building entirely new cities and neighborhoods from the ground up.

Retrofitting technology in old, creaky infrastructure can be extremely difficult. Starting from a blank page, founders, private developers and investors get to bake technology in virtually every aspect of their venture. These strategies are especially interesting for emerging countries with enough dough to consider these.

These greenfield opportunities can build housing at scale, but have humongous capital efficiency hurdles.

Examples of companies taking a first cut at this approach :

Culdesac. The company was founded in 2018 by Ryan Johnson (formerly founded Opendoor) and Jeff Berens (Economic development and urban planning specialist) and part of YC’s summer batch that same year. It’s planning to operate as the first car-free real estate developer and has broken ground on its first project in Arizona (Culdesac Tempe). They have raised an initial $10m seed capital to fund its operations only from top tier VCs: Khosla Ventures, Initialized Capital (reddit founder Alexis Ohanian), Bessemer VP and Y Combinator. One of the core pillars of their thesis is that the way we move defines the way we live, and that our options in that regard are changing much faster than urban planning and architecture altogether. As major capital cities in the US and Europe are undergoing a serious population leak, these developments could prove to be attractive to a high-earning portion of remote workers.

Venn. The company was founded in Israel in 2016 and kind of relied on the same idea as Culdesac. It started out focusing on completely rebuilding a portion of an outskirt in Tel Aviv, then pivoted to an extend coliving concept : instead of just focusing on your apartment community, the idea is to widen the network to a few blocks and sporadic apartments across a defined area. For example, the company acquired several properties in Bushwick, in an attempt to build a larger community. Operationally, it’s still very similar to other coliving startups where the core company operates developments and rentals and private investors chip in investment dollars in a separate vehicle. A much less riskier venture, but far less radical. Let’s acknowledge that building from-scratch neighborhoods is operationally very hard regardless of market tailwinds.

And other projects in consortia formats :

Belmont, Arizona. This one is an entirely new city in a place that has been sought for urban development since the 90s. As in anything Bill Gates touches, it has received its fair share of criticism since one of his investment companies, Cascade, took a $80m equity stake in the project for 24k acres of land. From an ambitious 290k housing target, the project has been downsized to a mere 100k and will be spread in a surface that covers pretty much the size of intramuros Paris. Many more developers have separate projects for the area and it’s unclear what will and will not be designed to be shared in the advanced infrastructure Gates initially wanted to build. Part of the criticism received was focused on (i) the social purpose of the newfound community : will it serve a high-earning crowd of qualified workers ? (ii) the fundamental problem with water supply and allocation in this arid locality, and the consortia’s elusive plans to deal with it

New Songdo. Songdo is a very particular place and embodies the crazy ambitions and thirst for development of South Korea. It has actually be gained over sea and heavily incentivized by the South Korean government as part of the Incheon Economic Free Zone. It’s one of the few cities that has installed an extensive network of tunnels to suck domestic waste directly to processing sites. Founded 10 years ago, this city is now home to 280k souls, but has been criticised abroad for its over surveillance, with many commentators pointing out that despite being overconnected, the city remained pretty isolated in its premise: Incheon is mainly a portuary zone outside of New Songdo.

Dholera. It’s really interesting to see projects like this one because India suffers from a western cliché that all of its cities, activity and administrations are extremely messy due to the formidable population growth it has experienced since going independent in 1947. Similarly to Songdo in South Korea, the Gujarat province administration created a special investment zone of about 920 square kilometers. It’s actually part of a larger plan from the Indian government to create a Dehli - Mumbai industrial corridor along a dedicated freight train line that would help with the logistics. Of all the greenfield projects I’ve perused writing this piece, it might just be one of the largest that has broken ground: the current population stands at 1,2m inhabitants. You might think it’s not that huge for India, but it’s a fifth of the province’s capital Ahmedabad, the sixth city of the country. Getting that much people to come is a careful work of planning the number of industrial “base” jobs and measuring the ripple effect in “support” jobs to size the development.

Looking at those projects and many more across the globe, I came to a number of conclusions :

A first caveat with these projects, especially in emerging countries, is that it is difficult to draw the line between the tempative soft power demonstration and the intent of actually attracting people and create a truly different community life in the newfound cities. Just like culture in a startup, it’s a very intentional yet extremely difficult and intricate process

Second, many of those projects raise environmental concerns because they tend to be located in areas that need ample rehabilitation (arid desert, swamped coastal zone) which we don’t know how to do in a respectful and carbon neutral manner for now. Hence, they are very carbon and capital intensive from the outstart.

Focus #3 - The increasing role of digital commons in smart cities

To oversimplify, digital commons have a very relatable real-life definition: Wikipedia, and for that matter, any other wiki. More broadly, it can have either one of two meanings :

A digital common can be a resource collaboratively developed and managed by a community. Wikis, creative commons licensed artworks and photos, open source software and repositories, protocol foundations. In many aspects, it’s a baseline of the development of internet itself: open and shared protocols and technologies benefiting the many

Now, outside of this textbook definition, I think there’s actually a second way of seeing it. A digital commons can also be a coherent mass of user generated content and the immaterial relationships that are attached to it. For example, you and a couple of your friends create a 🔥 Facebook meme group whose membership numbers go off charts very quickly. Now you have to moderate and organize it and it turns into a side hustle: what you have in your hands is a digital commons : it’s not yours, it’s community generated and you are not directly making money out of it

Digital commons make a lot of sense because they can help mitigate the isolation that our ever more connected world, surroundings and infrastructure inevitably create. It’s pretty difficult to quantify a sense of community, a study conducted by McKinsey found that using city-sponsored and feature-rich “citizen apps” increased the “feeling of connection to neighborhood community and local government” by 15 to 25%.

In my opinion, digital commons can be useful in these regards:

Connecting the local public to government.

Government tech initiatives often tend to be one cycle behind. For instance, many of us now interact in one-to-one or one-to-few communities and groups as a way to protect ourselves from traditional social media, seen as anxiety-inducing. But most governments still rely heavily on mainstream social media to vertically communicate with citizens

The landscape is slowly shifting as some city in the US are starting to move their information hotlines to apps designed for two-way one to one conversations. Not only does this allow a better tracking of mundane issues reported, the possibilities for expanding once usage is solid are numerous: weighing in on local policies or city budget, enticing citizens to mine data for their local government, etc

Countries like France still struggle a lot. There has been massive backlash against the anti-covid applications, whose sloppy design and late release have been fiercely criticized. This was particularly visible because the French government has positioned since the beginning of the Macron administration as the champion of tech businesses and progress for all, yet fails to deliver in time of utter emergency

Bonus - Citizen apps are also a great way to share a good laugh :

Person-to-person relationships and community building.

To fight the isolation and anonymity created by big cities where economic and social competition is very fierce, some platforms have been created to keep a hyperlocal focus and be a home for one-to-few interactions in public life.

The oldest example of this is apps like Meetup, whom I used a lot when I got in New York City with no friends to try and connect with locals. It’s platonical, and a little taboo to appeal to those apps to create connection and friendship but believe me, there is nothing more lonely than midtown New York in late February.

Neighborhood and community platforms like Nextdoor who catalyze and organise neighborhoods, mostly in suburban areas where it’s easier to go out and meet those in your direct surroundings

Dating apps, in a sense, were also a catalyst of city living and one-to-one interactions, but they are also to a large extent a mirror and catalyst for how we treat and view relationships, and all the toxicity that comes with it

Most of these person-to-person networks and platforms still are private endeavours, meaning that governments don’t get to listen in. That’s reassuring but it’s also a little frustrating that none of those can be a platform for community activism or political organization (e.g. voting groups)

Mapping the French ecosystem

The French ecosystem proves to be very vast: drawing from existing and partial maps, I was able to pin down c.180 companies.

I’m sure I missed plenty, which is why I encourage you to fill the Airtable form below if you’re building something in that space. Obviously, do let me know of any useful additions to make !

A few words to conclude

The future of cities certainly is a vast topic to cover, and the exceptionally rich French ecosystem is just one positive illustration of it. I believe there is more to come on all fronts, which I will explore in further articles.

I want to thank the many people who gave a look at first drafts : Ekaterina Geta for the incredible editing help, as well as Ariel, Nicholas, Sam, Rishi, Yann and all others 🙏

As per usual, free to ping me @LarocheUlysse or at my personal email larocheulysse@gmail.com ! 😄