⚠️ Announcement :

I will stop The Rookie VC for two weeks (until Thursday August 27th), a great occasion to take a break, reflect on the first 12 editions and prepare a survey and reader interviews to see how I can make this content for all of you !

To make up for it, I will be sending a digest of past issues on week 1, and a selection of my best articles and notes on different topics on week 2, supplemented by Twitter threads to summarize both !

Hi everybody !

I had the idea of digging into the topic of down rounds for three main reasons :

A discussion with my dear friend Julien Petit at Mighty 9 about the recent turmoil at challenger bank Monzo and the announcement of their down round and difficulties. I have prepared a longer mini-case study for you guys to read in this issue !

Down rounds will be common. Beyond the Monzo example, I had seen down rounds sprout all over the US and European tech news amidst the COVID-induced economic crisis. Though we have not yet seen this type of situation reported in France as of yet, down rounds for Series A and + companies could become quite common in the next few years. Hence the importance of bringing this topic to the table amidst less experienced investors like myself

Learning in public. I realized that I knew almost nothing about these situations, having never faced it as an investment banker nor an investor. The main goal of this publication is also to try and learn and teach my peers in public, so I figured this was a good occasion to educate myself on this topic

Before we dive into specific examples and advice I was able to gather on how to navigate this tough situation, let’s explore the concept and see how it bodes in practice.

What is a down round ?

In the fundraising cycle of a private company, a down round is simply the situation in which a company will raise capital at a price per share that is less than the price per share for its previous investment rounds. To practically understand this, I’ll give you an oversimplified example.

Joe has a SaaS company that sells software to travel operators. In the current context, his company has obviously suffered a very strong hit in terms of revenue. Pre-lockdowns, his MRR was growing 10% month-on-month and he expanded burn to prepare for even steeper growth, looking to raise a €30m Series B at €90m pre-money valuation, from the previous €10m round at €30m. Now, net revenue churn is upwards 20% and nothing is going to plan with no chances of a “V-shaped” recovery. The company still needs cash to survive, and the runway is getting shorter by the day.

The existing investors still believe in the long-term potential of their portfolio company, so they will agree to another €10m round but are demanding that the valuation be a mere €20m to €25m to account for the degraded growth perspective in the short to medium term. The management and the lead Seed and Series A investors and could also go look around for new money, in an attempt to reduce the write-down they will consent in their books.

What are the implications of a down round ?

Psychology and signal.

The VC and startup community is known to be obsessed by the idea of growth. For investors, explosive growth and returns to scale is their only shot at making significant money. Any clear negative signalling to flat or negative growth from one of their portfolio companies is a risk to their reputation and their value-add as a partner to entrepreneurs.

As Mark Suster puts it, “VC is a prisoner’s dilemma played across multiple games”: whatever you decide now as an investor (namely, re-investing or not) will not only affect future deals across your current fund (co-investing possibilities), but can also hurt your fundraising capability (LP reputation)

The more our French startup community gets interested in equity, the more it understands the advantages of working for a well-funded, well-run company. Hence, a down round can give quite a bad signal to top talent en route to joining Crew Dragon, only to find out they might be aboard the Challenger Shuttle. Employees are also typically not preferred investors and might not get a re-up of their shares as a result from the down round negotiation. Last but not least, down-rounds carry two side effects on the client side, first because financial stress means more bargains when renegotiating deals, second because it’s a bad psychological signal and might affect the way clients see their relationship to the company’s leadership, sales and customer service teams

Ecosystems (not communities, ecosystems in the sense of Ian Hattaway and Brad Feld) are influenced by the broader national culture they geographically operate in. Hence, it never is a good sign in cultures where failure is frowned upon and perceived as possible misconduct and a lack of hard work. Although most investors and clients can see past their cultural bias, the media tends to amplify failure stories negatively and with a suspicious look. For your information, there has been no nation-wide FailCon in France since 2014 (!)

Anti-dilution rights.

Anti-dilution is a protection that preferred investors use to make sure they will be entitled to a larger stake in a company in the event of a down round. As you could guess, the goal here is to compensate for the reduction in value of the company by granting the existing investors a larger stake

Anti-dilution rights can take multiple forms, but the most observed are either ;

“Full-ratchet”. From being a Louisianian slang word, the word ratchet evolved to many meanings. In the realm of venture capital, it designates a legal clause that entitles the holder of preferred stock to convert to an amount of common shares equal to the amount of its prior investment divided by the current share price. Here’s a little, very simple schema below to summarize what full ratchet entails. As you can see, ratchet fills one simple objective: it nulls the negative impact of a down round for the investor at the expense of common stockholders, who will be further diluted.

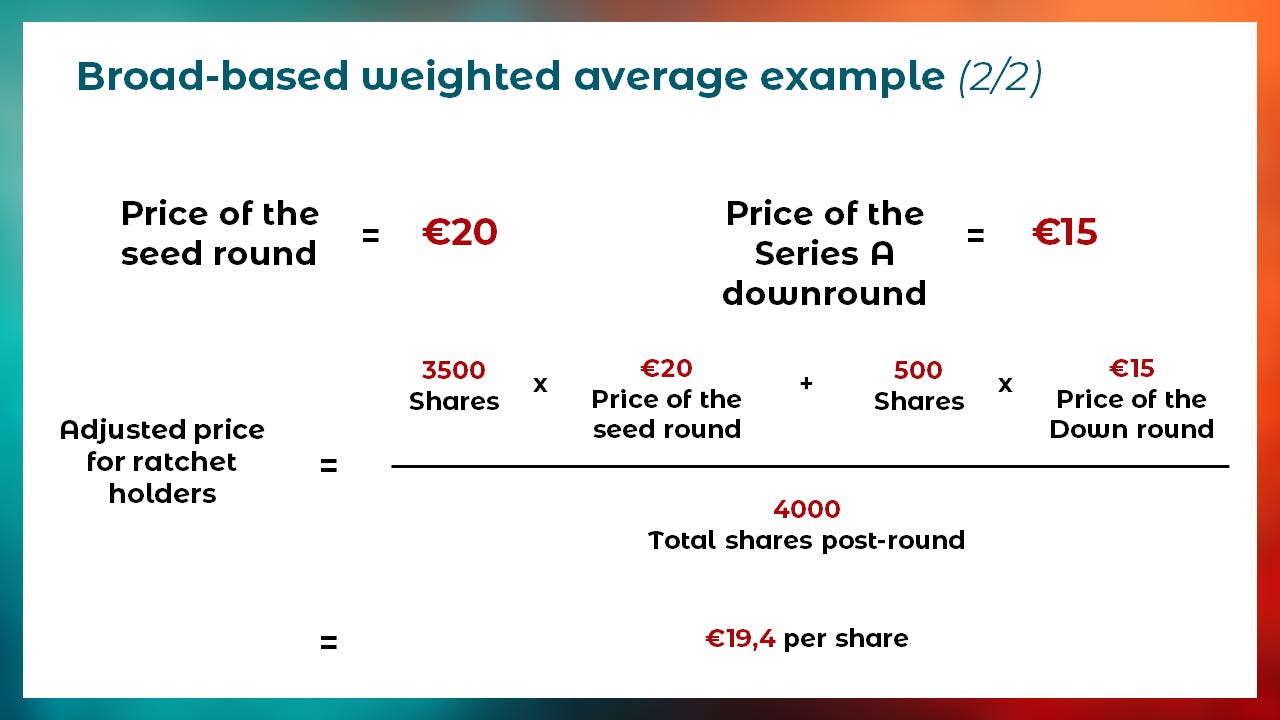

“Broad based average”. This mechanism also implies that preferred stockholders will have the right to convert their stock to a greater amount of common shares. The difference here is that this number will be based on an average taking into account the entire number of shares outstanding for the company, at the price they were at the last round. Intuitively, you can see that the broader the base for the average, the lesser impact it will have on the price at which you can exchange your preferred shares for common shares. I’ve also included a very simple example below so that you can grasp the math behind it all !

“Narrow-based average”. Narrow-based averages are just a variant of broad-based averages. Instead of taking the entire number of shares into the calculation, they just take the number of shares issued at the last round and their price. See an example below !

Fund accounting. The last aspect and major implication of down rounds is that VCs must account and report unrealized and realized portfolio performance to their LPs biannually or quarterly. That implies that unrealized investments are marked up or down, depending on their Fair Market Value. As any VC firm manages and is raising its next fund at any given point across its lifetime, any significant markdown is a bad signal to LPs, that can hurt the effort to secure another fund. General Partners managing the fund can also be deprived of some of their distributions that are based on unrealized performance. Hence, VCs will not risk a down round if they think the company can not get back on its feet quickly and raise new money within the lifecycle of the fund, effectively allowing for a future mark-up.

What are typical down rounds scenarii ?

An “ordinary course” down-round. This scenario is the most simple, or the least complicated one. In most cases, you can suppose that under this scenario, there will be an alignment in the investor group on price and on what terms should be traded for a moderate discount versus the last round. On the company’s side, the team must be aligned on the terms they’re willing to trade with. In either case, dealings are done internally and neither side has really much of a vested interest of not playing ball with the other. Deals end up being done with moderate to benign bargaining games. Under this normal scenario, everyone will invest pro-rata ownership percentage prior to the round, and gets whatever anti-dilution rights (see above) will grant them.

“Hardball” down rounds. The defining characteristic of a hardball down round is that the company or the context doesn’t enable a clear path to an internal consensus. Here, the most probable and frequent mishappening is team-related. In a lot of cases, it will mean one thing: new money in the round usually means the investor will get to push for ousting the current CEO / founding team and his direct reports. That means the newly appointed CEO and team will have the most power, because they’re an essential enabler for the success of the new money in the round: they stand to be awarded and incentivized. Same goes for overperformers that are chosen to replace sacked employees. The existing investors have little power but their veto power, because they can’t argue too much on terms because their chance not to mark down the deal in their books is dependent on new money investors. Finally, the ousted managers or founders are the real losers in this type of situation and will foot the bill so that existing investors wound up in a decent place, while retaining little to no equity due to anti-dilution rights

I am most certainly not an expert of these situations, having lived through none as a non-founder and a pretty young investor (8 months in the making, woop!). But I have scoured the internet and looked for the advice of experts, from repeat founders of successful businesses, lawyers and lawmakers that support entrepreneurs in dire times of their companies’ lives.

Here are a few findings that I think are interesting :

Legal

The discussion around the most plausible scenario to go with in a down round must be anticipated by weeks ahead, when possible. It’s also very important to hone consensus from the day the idea is laid on the table, so that all preferred investors will feel aligned with the anti-dilution mechanisms and the route the founding team and early investors choose to take

There are many legal clauses for voting and pre-emptive rights of existing shareholders that must be overwritten. You can’t afford to be blocked by time constraints attached to existing pre-emptive rights notice periods, timetables for pay-to-play obligations, etc. It’s generally important to remove any bottlenecks that might slow down a consensus with great momentum

Process and negotiating leverage

As we’ve previously mentioned, it’s very important to generate a broad consensus amongst existing investors about price, conditions and presence (or lack thereof) of new money in the envisioned down round. Many founders that have had to face a down round say that consensus creates positive leverage. CEO of used car marketplace Shift George Arison describes it best : “It created a positive leverage in our discussions with new investors, because the capital cleanup had been done internally already,” says Arison. “They weren’t coming in to try and force terms that people were unwilling to accept. Rather, it was like, ‘Okay, this is my set of terms, based on the terms that you’ve already said you’re willing to accept.’”

As a founder, you must give your existing investor group to waive troublesome clauses such as full ratchet anti-dilution rights. The first and best reason is that it can serve to protect the team and employees against a harsh dilution and de-align them with the mission, virtually barring any return to an acceptable growth course. An aligned partner will almost always see how easier, re-negotiated anti-dilution rights are always a better idea and are also a vote of confidence for any new money investors coming into the round

Taking one for the team

In startup communities where employees are usually not very interested in equity incentives, there is a clear risk to leave out the albeit important question of employee equity and incentives while thinking about a down round. Some founders will consider that this is a strictly financial course of action and that employees are secondary to investor consensus

But here’s the kicker: they are most certainly not. It’s an ideal occasion to get in the arena with a carefully designed, sincere communication plan for employees. You will need to bear in mind that the bigger the company you run, the more risk there is your narrative leaks out to the outside. Therefore, it has to reflect what you would say to any counterpart outside your walls, be them journalists or other commentators.

This type of event will usually be paired with cost haircuts and layoffs. It’s important to (re)design a system where the top performers can get option refreshes if they play ball in the anticipated recovery of your company, which the down round will fund

Airbnb.

Earlier in April, news broke that Airbnb would be doing a $1bn debt funding deal with US private equity houses Silver Lake and Sixth Street. The terms were as follow: the debt is junior to pre-existing debt and bears a LIBOR + 10% annual interest, along with warrants on 1% of Airbnb’s total equity post-round.

Amidst the crisis, the household name marketplace has obviously undergone serious turmoil, and had to fund $250m on refunds alone on its own cash since the beginning of the lockdown, with that figure likely to have expanded significantly afterwards. The company’s last round of funding was a $442m Series F funding with its historical investors (a16z, Sequoia) and others (TCV, Capital G, Bracket Capital) at a $31bn valuation. The alleged $18b valuation for the current round would imply a 42% hit.

Now my biggest questions are: How well can Airbnb recover from the downturn ? Will the company lose a significant (>20%) portion of its inventory in countries that are still closed ? At the time the investment was made, those would have been valid points. But with Europe slowly reopening and the US in complete chaos with many still out and about and extreme leadership uncertainty, it’s still very hard to tell if the “V-shaped” recovery that Airbnb seems to have going is a good trend. Regardless of travel conditions, I personally believe that Airbnb has a solid flywheel that is very much adaptable to local tourism in most of the biggest markets.

It’s difficult to judge the company’s reliance on out-of-country travel and the recovery that it will or will not experience going into, 2021, nor is it easy to evaluate the growing trend of local, intra-national or intra-communitarian (e.g. EU or Schengen-contained) tourism as we do not yet have data points for at least 1 semester post-lockdowns. The question of inventory stickiness is central: if Airbnb can keep hosts on the platform but give them opportunities to bridge the gap with longer-term tenants, it has a decent pivot to rely on. Packy McCormick has even explored an Airbnb and Zillow deal on his latest edition of Not Boring, which I find to be a particularly good hedge idea and a great vision for “frictionless real estate” - Go read it, it blew my mind!

Monzo

Monzo is a UK-based neobank and has the strong particularity of having been funded in part by its users, through successive “flash crowdfunding” sprints. The first occurred in 2016, raising £1m in 96 seconds, quickly followed by a £20m round closed in just two days and a half on crowdfunding platform Crowdcube.

Monzo raised £60m at a £1.25bn valuation, which is a 40%+ drop from its previous valuation standing at £2bn+ following the £113m June 2019 fundraising round with Accel, General Catalyst and YC and others

There has been much worry amidst the crowdfunders, as many did not properly grasp that the anti-dilution provision also included them - At least as far as I could read in the articles of association and the prospectus available on Monzo’s site. This means, as the community members coin it, that nobody will be effectively “eating the devaluation” on behalf of other institutional investors on the cap table such as Accel, General Catalyst, YC, etc.

Monzo has been heavily prompted by the FCA to continue fulfilling its capital requirements as a fully licensed bank under Basel II rules (8% of its risk-weighted assets must be held in liquid cash), which will cause regular raises until the company is on a good trajectory to turn a steady profit

Monzo is suffering “challenger bank fatigue”. Acquiring customers for a neobank has never been cheap, especially once you break out of the initial referral loop that many competitors will use as a kick-starter. But the fatigue means you either have a very convincing edge (fractional trading, fancy cards, niche positioning), or you’re condemned to burn even more cash in acquiring customers until you are big enough to start charging significant money

There is a user growth vs. lending revenue cultural dilemma. The mentality and product intent to always grow faster and bring on more users while ensuring sound retention is a world apart from the mundane business of lending capital, which is still limited to £3k loans on Monzo for now. At some point, the company will have to find a way to shift gears to ensure that it can show something else than linear, subscription-driven growth. Until then and as coined by FT journalist Jamie Powell, it’s “a bank that doesn’t want to be”’

I hope you liked this issue, and if you have any suggestions to make please do ping me on Twitter ! :)

Ressource list :

Airbnb Paying More Than 10% Interest on $1 Billion Financing Announced Monday, WSJ

Zillbnb, Never Boring by Packy McCormick

Monzo: the bank that doesn’t want to be, FT Alphaville, Jamie Powell

Tips to Navigate a Down Round Equity Financing, Winston & Strawn LLP

Are you ready for the coming wave of VC down rounds?, Techcrunch

How VCs Could Try to Rip-Off Founders During This Crisis, Fred Destin

The Damaging Psychology of Down Rounds, Mark Suster

Want to Raise Venture Capital More Easily? Clean Up Your Own Shite First, Mark Suster